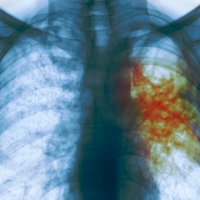

Once dubbed “Ebola with wings”, tuberculosis resistant to standard antibiotics could finally be on the run.

A new regime of seven antibiotics has been shown to vanquish multidrug-resistant tuberculosis (MDR-TB) within just nine months, less than half the time it takes with current treatments. One of the antibiotics – clofazimine – was until recently used mainly to treat leprosy.

In all, 821 of the 1006 people with MDR-TB treated with the new course of drugs across nine African countries were cured in a two-year study. “That’s 82 per cent, which is excellent, and with treatments lasting just nine months,” says Valérie Schwoebel at the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease, which unveiled the results this week at an international conference on lung health in Liverpool, UK.

The standard treatment that it could now replace cures only 55 per cent of people, with many dying because they abandon the prolonged treatment of 20 months or more. The new regime is also cheaper: Schwoebel estimates that it costs less than $1000 per person, compared with at least $3000 for the current treatment.

The results replicate those of earlier, smaller studies, providing extra reassurance that the treatment works. Preliminary results from the trial released in December prompted the World Health Organization in May to recommended replacing the old treatment with the new regime.

“With strong evidence now showing that this regimen is the most effective available for treating multidrug-resistant forms of TB, the next step is for countries to begin widely implementing this new approach,” said Arnaud Trebucq, who presented the results in Liverpool.

“The new regime is nice, because it’s less toxic and much shorter,” says Mario Raviglione, director of the WHO’s global TB programme. But he cautions that it can only be given to around a third to half of all cases worldwide, because it will not work if people are already resistant to certain “second-line” drugs used to treat tuberculosis if standard treatments fail. Provided that people are only resistant to the classic antibiotics rifampacin or isoniazid, the regime can be used.

Raviglione says that in most African countries, resistance to second-line drugs remains rare, so the regime can be widely used. However, such resistance is common in the former Soviet Union, so the regime will be less applicable there.

Global threat

For now, the disease remains a global threat. MDR-TB continues to spread, with many people not receiving any treatment, according to the WHO in its Global Tuberculosis Report published this month. “The crisis of MDR-TB detection and treatment continues,” it warns.

Of 580,000 people newly diagnosed with MDR-TB in 2015, only a fifth received the existing therapy, and 250,000 died. Three countries – India, China and Russia – account for almost half of all cases.

Schwoebel says the main reason for the continued spread is the failure of people with ordinary TB to complete their six-month treatment regime. The result is that the bacteria survive and develop resistance, then spread to others.

“This crisis is created through countries with badly functioning programmes,” says Schwoebel. “So the population with MDR-TB is growing despite the fact we have good tests, good diagnosis and now improved treatments.”